Circuit Design for Manufacture or Application?

Circuit Design for Manufacture or Application?

Design for Manufacture or DFM has been a common topic for circuit designers for a long time. Before manufacturers started publishing their capabilities on websites, a trip would be scheduled to the supplier so that designers could talk with the operators at each fabrication station and the production engineers to better understand their supplier’s capabilities and limitations. That, it was surmised, would make designs better from the customer and save time during the review process. The customer would learn what limitations their supplier had on things like minimum plated hole sizes, minimum annular ring, minimum line width/space and more. On the surface this seems like a very valuable thing to do. It improved the communication between customer and supplier and theoretically improved the quality of the circuits and design cycle time as well. However, the compromise was always done by the customer!

Of course, the circuit must be manufacture-able! But is it best for the customer to compromise their design to meet their supplier’s limitations? Remember, the customer will assemble and insert these circuits into their coolest new products with the intent of selling thousands or millions of them. With that fact in mind it would make more sense for the supplier to compromise to meet the application’s requirements to give it the best chance of success. That, of course, is difficult for a circuit manufacturer. It is far easier for a circuit manufacturer to adhere to a strict set of capabilities and design limitations so that their factory runs as smoothly and efficiently as possible all the time. As well, all customers want the lowest price possible for their circuits and being efficient is an intuitive response.

But what’s more important to the customer? Is it the price of the circuit? Or is it the best design for their new product? The customer might argue both. It would be hard to disagree.

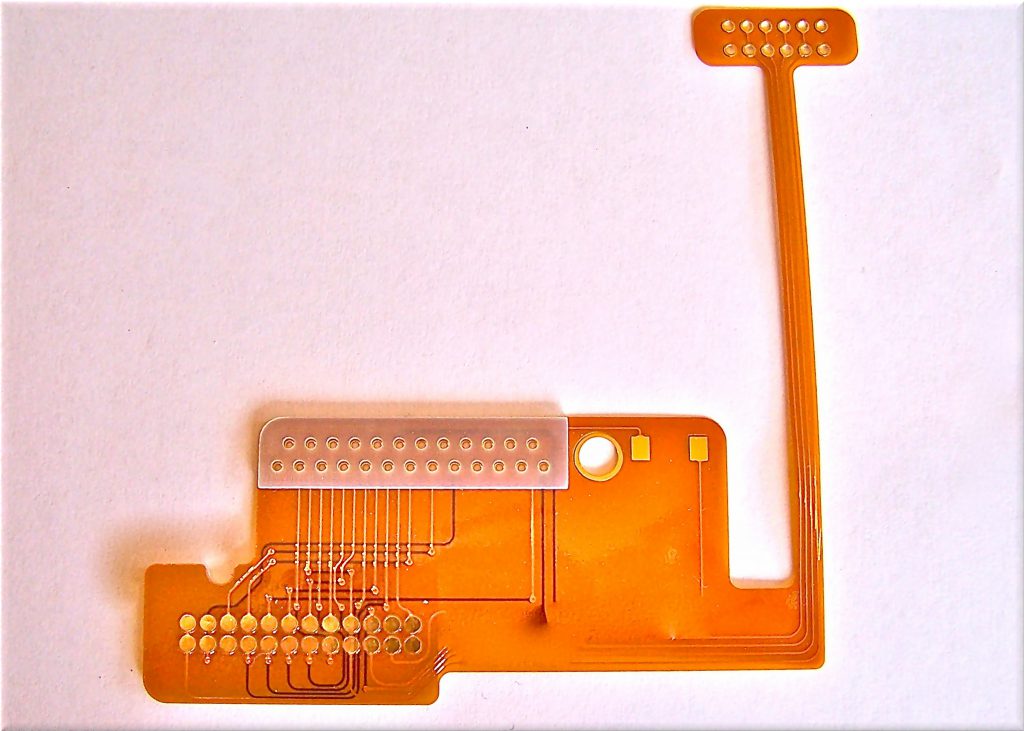

Let’s look at two theories in practice with a similar design. In the typical DFM model, a circuit would be designed with the supplier’s specific capabilities in mind. For instance, the board size may be increased from the engineer’s request to make room for the supplier’s minimum trace width/space limitations. Or simply the space between copper and the edge of the circuit. Or to make room for larger diameter via holes because of the minimum hole size and annual ring requirements. These are not uncommon specifications defined as limitations from a circuit manufacturer. However, let’s look at the outcome to see how the product may be affected. If the board size must increase then, in a typical situation, the entire product size must increase. In our current product environment of smaller is better, that would be a significant compromise for the customer to make simply to stay within their supplier’s standards.

Let’s consider an alternative theory. Design for Application or DFA. If DFA is used in place of DFM in the same scenario, the board may be designed as intended and the circuit and product may remain at the original size it was imagined. The long tenured supplier may choose not to make a circuit with these specifications. Or they may choose to look outside their standards and improve their processes to meet them. The advantages for the circuit manufacturer include the ability to continue to service a good customer, to expand their capabilities and challenge their limitations. This may cost the customer, initially, in the form of a higher priced circuit. However, they would have the opportunity to compare the increased circuit cost to the cost of a larger product profile and its acceptance in their industry. Product development engineers will appreciate the chance to weigh all the options intelligently, thereby landing upon the most valuable decision for the product and the company.

Design for Application has its challenges to be sure. The operators at the circuit manufacturer must be willing to try new processes and discuss all options. They must argue the pros and cons with equal enthusiasm in order to eliminate long standing biases. And management must be able to sell the idea of change as good for both the company and its employees. That’s not a simple task. As well, the customer must understand that their current requirements fall outside of their supplier’s standards and be patient and cooperative while they strive to improve.

This idea challenges decades of success of circuit manufacturers to educate their customers. But, it is just as exciting for the customer to educate the supplier. When they have suppliers that are willing to work with them and discuss available options as opposed to demanding the design be changed to suit their abilities, it should provide increased communication and maybe loyalty as well. The situation is a win for both parties. The customer gets the best possible solution to their challenges and the supplier improves and expands their capabilities. As time goes on, it would be reasonable to assume that the supplier’s standards and limitations may be improved permanently and costs may be reduced for these improvements.

Design for Application. it’s a new idea, but one worth exploring!