Flexible Circuits Returns: Negative Experience or Valuable Opportunity?

Customer Returns Valuable to the Manufacturer?

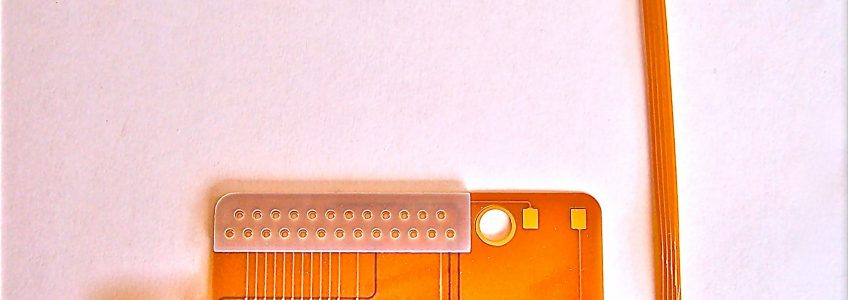

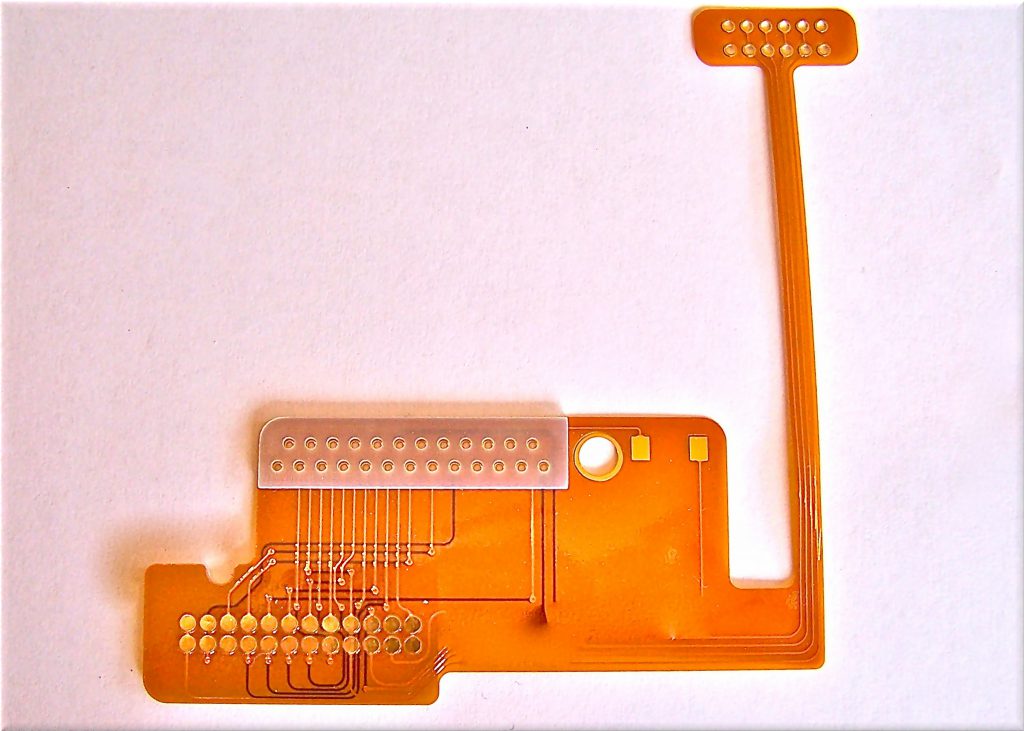

Tramonto Circuits designs, supplies and assembles flexible circuits. These circuits are important to a lot of the new technology that we see today because they are lightweight and by definition, flexible! In an article published in Flex007, a new magazine put out by the folks at iconnect007, we discuss customer returns and the value they bring to a manufacturer. Returns in the flexible circuit industry are typically viewed negatively, but John Talbot discusses a different view point that defies that stigma. Please read the full article below.

Consider This: RMAs, a negative experience or valuable opportunity?

RMAs are disruptive and tedious

Returned product is inevitable if you work in manufacturing. That does not imply that it is easy to address. No matter what the reason for the returned material, it disrupts the normal flow of the quality and manufacturing teams. An inspector must first review the defect and agree that it is indeed a defect. This seems a simple task and can be if the material doesn’t match a customer specific requirement. However, if the material must adhere to an industry wide standard, such as the IPC in the circuit industry, it becomes a little more tedious. In most cases the manufacturer will be more familiar with the specification than their customer. Also, they are more likely to keep the latest revision of the requirements in their library. This can cause a situation where the customer has identified a reject that isn’t agreed upon when compared to the standard it was built to. Tedious indeed! As well there are other cases that have been witnessed by the author that create a less than easy situation. For instance, if the customer sends back rejected material that wasn’t built by your company. This is typically easy to determine by company markings. Or they send back materials that have obviously been damaged by handling at their own facility. It complicates an already difficult process.

How it happens

In the flexible circuit industry and any other industry for that matter, there are times when all of the material delivered to the customer does not meet the specifications. This can happen for a number of reasons and typically depends on the final inspection process. Two common final inspection processes used are sampling and 100%. When a product utilizes the 100% inspection process, every part that is shipped to your customer will also have been inspected. A sampling process is intuitively a partial inspection, typically 10%-25% of the total, and is used on products that have a long history of zero defects. The product may have started out with a 100% inspection and proved over time that the manufacturing process was solid enough that it didn’t output any rejects. Another time when the sampling practice may be used is on very high volumes where 100% inspection would prove too costly. In either case, there are times when a part could be shipped with a defect. In the case of sampling, it’s obvious that a defect could be shipped because not all of the product is inspected at the final stage. With the 100% inspection process one would think that nothing shipped would have a defect. However, it’s understandable that an inspector could mistakenly place a rejected circuit in the approved container for shipment to the customer. Or simply miss a defect. No matter the cause, materials that reach the customer that do not meet all specifications should be addressed and rectified expediently.

So, what is to be done?

A typical process for addressing a customer request is to issue a Returned Material Authorization (RMA) and ask them to send the product back for re-inspection and confirmation. It is best, in the author’s opinion, to trust your customer and treat them with utmost respect. At this time more than any other they count on you to help resolve a problem. Communications should be swift and thorough in order to assure your customer that you are their partner when things go wrong as well as when they are going smoothly. Once the returned material has arrived, it should be confirmed and if necessary, the entire shipment should be inspected in order to segregate all products that are suspect. It is easy at this point to cut corners because of the disruption it causes. You can fault the customer’s employees for handling improperly. You can state defiantly, that all products meet the requirements that we have on file and blame poor documentation. Or you can take a deep breath and handle the issue for the customer the same way you would handle the issue if it were yours! After all, they trust you enough to build their precious products. Assistance when things are not quite right should be the least they expect.

Root Cause Analysis

With the material in hand and the non-compliance recognized and accepted. Let’s get down to finding out what happened. Or in the case of a recurring product, what has changed. The quality team is the first to see the returned products. But after the reject is identified they will need to recruit assistance and expertise from the manufacturing team. An inspector may be very good at identifying the non-compliance, but it will ultimately take collaboration with the team that builds the product to identify the root cause. This is a very important step and may take a lot of time and patience. There are many times when the first cause identified is not the culprit. Each theory should be identified and tested to verify the cause. It is imperative to find the root cause of the defect and test solutions until the best one is agreed upon. As you may guess at this point, it is not always an easy process. Thus, the disruption mentioned above. The manufacturing team must interrupt their ongoing schedule to help the quality team who has also interrupted their schedule to find definitively both the root cause and the corrective action taken to resolve it.

Document and Verify

Now that all of the hard work has been done to identify the cause and solution, it is time to document our findings. This is done formally on a so called Corrective Action Report (CAR). During the arduous testing that was done to confirm the findings and then resolve them, a lot of information was gathered. That information is invaluable to the manufacturer. It has added experience and knowledge to the team that could not have been offered without going through the process properly. A typical CAR will include the initial findings from the customer, analysis done by the supplier, corrective measures that resolve the current problem and preventive measures that assure the same issue is not repeated on future builds. At this point one may think that the process has been completed. However, the resolution should be tested and verified for at least three future builds to confirm its validity. At that point one may be confident that the root cause was properly identified and resolved!

Negative experience or valuable opportunity

Non-conforming material that is sent back by the customer can easily be interpreted as a negative experience. However, if it is perceived as an opportunity to learn and support the customer it becomes a much more pleasant and satisfying endeavor. The knowledge gained, however painful it may be, is an asset to the manufacturer. It can and should be used to inform and educate the entire team, from the designers to the final inspection team and all that touch products in between. When a story is reported in the news today about a stranger that helped another it is termed a “feel good story”. In the manufacturing industry, the feeling is the same each time we resolve a customer issue with confidence and enthusiasm.

Consider This: Circuit Design for Mfg or Application

Circuit Design for Manufacture or Application?

Circuit Design for Manufacture or Application?

Design for Manufacture or DFM has been a common topic for circuit designers for a long time. Before manufacturers started publishing their capabilities on websites, a trip would be scheduled to the supplier so that designers could talk with the operators at each fabrication station and the production engineers to better understand their supplier’s capabilities and limitations. That, it was surmised, would make designs better from the customer and save time during the review process. The customer would learn what limitations their supplier had on things like minimum plated hole sizes, minimum annular ring, minimum line width/space and more. On the surface this seems like a very valuable thing to do. It improved the communication between customer and supplier and theoretically improved the quality of the circuits and design cycle time as well. However, the compromise was always done by the customer!

Of course, the circuit must be manufacture-able! But is it best for the customer to compromise their design to meet their supplier’s limitations? Remember, the customer will assemble and insert these circuits into their coolest new products with the intent of selling thousands or millions of them. With that fact in mind it would make more sense for the supplier to compromise to meet the application’s requirements to give it the best chance of success. That, of course, is difficult for a circuit manufacturer. It is far easier for a circuit manufacturer to adhere to a strict set of capabilities and design limitations so that their factory runs as smoothly and efficiently as possible all the time. As well, all customers want the lowest price possible for their circuits and being efficient is an intuitive response.

But what’s more important to the customer? Is it the price of the circuit? Or is it the best design for their new product? The customer might argue both. It would be hard to disagree.

Let’s look at two theories in practice with a similar design. In the typical DFM model, a circuit would be designed with the supplier’s specific capabilities in mind. For instance, the board size may be increased from the engineer’s request to make room for the supplier’s minimum trace width/space limitations. Or simply the space between copper and the edge of the circuit. Or to make room for larger diameter via holes because of the minimum hole size and annual ring requirements. These are not uncommon specifications defined as limitations from a circuit manufacturer. However, let’s look at the outcome to see how the product may be affected. If the board size must increase then, in a typical situation, the entire product size must increase. In our current product environment of smaller is better, that would be a significant compromise for the customer to make simply to stay within their supplier’s standards.

Let’s consider an alternative theory. Design for Application or DFA. If DFA is used in place of DFM in the same scenario, the board may be designed as intended and the circuit and product may remain at the original size it was imagined. The long tenured supplier may choose not to make a circuit with these specifications. Or they may choose to look outside their standards and improve their processes to meet them. The advantages for the circuit manufacturer include the ability to continue to service a good customer, to expand their capabilities and challenge their limitations. This may cost the customer, initially, in the form of a higher priced circuit. However, they would have the opportunity to compare the increased circuit cost to the cost of a larger product profile and its acceptance in their industry. Product development engineers will appreciate the chance to weigh all the options intelligently, thereby landing upon the most valuable decision for the product and the company.

Design for Application has its challenges to be sure. The operators at the circuit manufacturer must be willing to try new processes and discuss all options. They must argue the pros and cons with equal enthusiasm in order to eliminate long standing biases. And management must be able to sell the idea of change as good for both the company and its employees. That’s not a simple task. As well, the customer must understand that their current requirements fall outside of their supplier’s standards and be patient and cooperative while they strive to improve.

This idea challenges decades of success of circuit manufacturers to educate their customers. But, it is just as exciting for the customer to educate the supplier. When they have suppliers that are willing to work with them and discuss available options as opposed to demanding the design be changed to suit their abilities, it should provide increased communication and maybe loyalty as well. The situation is a win for both parties. The customer gets the best possible solution to their challenges and the supplier improves and expands their capabilities. As time goes on, it would be reasonable to assume that the supplier’s standards and limitations may be improved permanently and costs may be reduced for these improvements.

Design for Application. it’s a new idea, but one worth exploring!